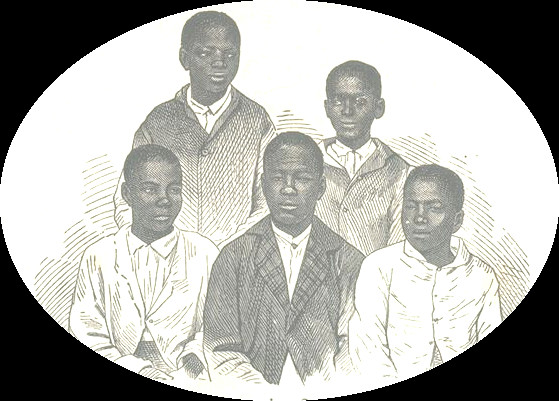

Contemporaries of Christoph Muhongo

Christoph Muhongo, Josef Ingula, Lappland Heinrich Tjindimbue, Hendrik Djuella (End of the 19th Century)

Abducted by Explorers

The RMS had already written about the “evil influences in the midst of disbelief” in connection with Josaphat Kamatoto’s trip to Germany. This assessment prevailed in the governing bodies of the RMS and must have been the underlying reason why there are no records of any Evangelists from the Ovaherero, Nama or Damara congregations who were taken to Germany and trained in Barmen. It was not until 1962/1963 that a Namibian pastor, Elifas Eiseb, came to Germany for further training.

Mission societies, who brought Africans from their mission areas to Germany and trained them in their seminars had very different experiences with their ventures. The most famous visitor who came to Germany, though not as a student, was Uerieta (Johanna) Kambauruma Kazahendike. She came to Germany from Hereroland as an employee of Carl Hugo Hahn who had taken her along on his second periodic home leave to Germany in 1860. Hahn’s plan was that she was to help him with the final proofreading and publication of biblical stories, an Otjiherero grammar and a German-Otjiherero dictionary. On Sundays, Hahn took her along to services and mission festivals. However, she became seriously ill during the time, apparently because she did not feel comfortable, and travelled back to southern Africa before the Hahn family did.

According to the records, four Africans stayed at the Mission House in Barmen at the turn of the 19th/20th century and spent various lengths of time there for training. They were: Hendrik Djuella (originally from Cameroon), Lappland Heinrich Tjindimbue (from Central Angola), Josef Ingula and Christoph Muhongo (because of their mother language being Oshimbundu, they were probably from South Angola). All four were not from Namibia. Telling their stories alone would be interesting enough, because as early as the 19th century they demonstrated the new spaces of a globalised world. German explorers had brought the four – independently of one another – as children or adolescents to Germany from different parts of Africa. As long as they were of use to the travelling gentlemen, such as Count von Rex or Major von Brelow, being living exhibits of an exotic collection, they made effective publicity when giving lectures, attending events or on marketplaces. But as soon as the novelty wore off with the public, the explorers lost interest in their “exhibits” who were by now young men.

Because of lack of interest in the future of the young men their “owners” got in contact with churches or other charitable institutions to get rid of them. In these circles the absurd-sounding idea arose to train them as missionaries and to send them back to Africa as local workers. They ended up in the mission house in Barmen and were later taken with RMS missionaries to Southern Africa. None of them completed the intended training in Barmen, and nor were their services as Evangelists in line with the ideas of the local missionaries. Three of them – Muhongo, Tjindimbue and Ingula, now listed as “Ovambo youths” – were students at the Augustineum at the end of the 1880s. This arrangement did not prove to be very successful, as Muhongo did not fulfil the requirements and the other two were soon dismissed because of disciplinary problems. Due to their origins from the Oshimbundu-speaking area of Angola, RMS missionary Brincker saw a possible use for them in the Ovambo Mission and offered them to the Finnish Mission Society (FMS), which had been active in Ovamboland since 1870. However, the FMS rejected the offer with thanks, because they probably anticipated forthcoming problems.

According to Brincker, this rejection by the FMS caused the RMS to open up its own new mission area in Ovamboland. According to the time-tested method of sending local Evangelists into a new territory as a vanguard, Muhongo, Tjindimbue and Ingula were now thought to be the ideal Evangelists who would make it possible to advance into this new mission area.

Indeed, in 1891 Muhongo, Tjindimbue, and Ingula together with three young RMS missionaries travelled to the far north of Namibia to conduct pioneering mission work amongst the Okwanyama. With their language abilities and practical experience, the three became indispensable helpers for the inexperienced missionaries and should therefore, in mission history, be regarded as co-founders of the Kwanyama Mission as well as of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Namibia (ELCIN). Nevertheless, on the long journey to Ovamboland the missionaries discovered that they were not dealing with highly motivated Evangelists. Their hopes that the young men would through their preaching and interpretation, become important pillars and agents of the new religion, were dashed. Upon arrival in Ovamboland the missionaries soon noticed that the Evangelists seemed to be more interested in securing their own livelihood in the new environment than constructing a mission station. Annoyed, one of the missionaries wrote to Barmen:

You [meaning the Council of Delegates of the RMS as addressee of the letter] think that I should have known what kind of companions the boys are that were given to us from Hereroland and I should have known better to be much stricter with them and keep them under supervision. [...] I can say that here we have much more to fear of them than they of us, because they simply go their way and lie around with the chiefs, just as they please.

Muhongo was the only one who, many years after their arrival in Ondjiva, was still mentioned as an Evangelist in reports of the missionaries. He seemed to have been given farmland by Chief Uejulu, but his status was extremely insecure and dependent on the missionary’s presence. Whenever the missionary was not there, an attempt was made to drive Muhongo off his land.

The experiences of Christoph Muhongo in Odjiva and those of Josaphat Kamatoto, who, at about the same time was an Evangelist in Okahandja, are worlds apart. What were the factors that made Josaphat Kamatoto an important Evangelist in this period? Josaphat Kamatoto was a second-generation Christian and the contents and rituals of Christianity, as imprints of his time, were familiar to him since his childhood. He grew up in the immediate vicinity of the German colonial authority, whose German officials, having the same background as the missionaries, may have seemed familiar to Josaphat Kamatoto. He spoke Otjiherero, Nama, Dutch and German. With his language skills he was needed by colonial officials and officers for negotiations and expeditions. This opened up new income opportunities for him – in addition to his meagre Evangelist/teacher salary of 400 marks (£ 20) per year, paid by the parents of his students. This regular income made him materially less dependent on the RMS. On the one hand, RMS missionaries advocated good relations between Evangelists and authorities and settlers, but on the other hand they also saw the risk of Evangelists switching to better-paid jobs or neglecting their work.

More important than these colonial connections, however, were Josaphat Kamatoto’s roots amongst his own people. The ancestors of Kamatoto can be traced back by name until the 16th century. The fact that the names of eleven generations had been preserved in oral tradition can confirm the importance of the family in the history of the Ovaherero. Josaphat Kamatoto took part in the victorious battles for the Ovaherero against Hendrik Witbooi in Otjitueze and Otjisauna in 1892. After three years of training and teaching at the Augustineum – through which he himself was able to shape young Evangelists – he came to Okahandja already a recognised Ovaherero personality in an Ovaherero community (which included many Damara). He was later transferred to Otjiseva. There he married Martha Kavari who became an important co-worker in the congregation. His wife, like Josaphat Kamatoto himself, came from a famous royal Ovaherero family. She was born into a Christian family as both her parents, Stephanus and Sarah Kavari, had been baptised when Martha was born. She grew up in the household of missionary Johann Jakob Irle and the marriage strengthened the local Ovaherero network of Christians in the second generation. In his next position at Ojtikukurua/Osire – which was a branch station of Okahandja – he was no longer under the constant supervision of a missionary.

Through his stay in Germany, he was one of the few Evangelists who could have obtained first-hand information and a realistic picture of conditions in the country. This would have changed his view of the Germans in his own homeland in two respects. On the one hand, Kamatoto would have seen the German missionaries with different eyes. He would have realised that the one-sided narrative of the German Christian nation who sent the missionaries to the “heathen” Africans could no longer be upheld, and the much-loved “solemn fathers in Barmen” were in reality not more than volunteers in an association without much political and social significance – in a seemingly non-Christian country as measured by the noble ideals of the missionaries who represented their country. On the other hand, Kamatoto would have realised that the German state possessed considerable military power, although its colonial power was only poorly represented in Namibia in 1895. The arranged visits to the military parades in Berlin would not have failed to meet their objectives.

At the beginning of the German-Herero War, Josaphat Kamatoto joined the Ovaherero combatants. Like the Ovaherero chiefs and their followers, the leading Ovaherero Christians and their congregations followed Samuel Maharero’s call and assembled at the Waterberg. The Christians, among them Josaphat Kamatoto, convened in their own camp alongside the big crowds of Ovaherero fighters. In April 1904, during the preparations for battle, Kamatoto met the RMS missionary August Kuhlmann and his family near Oviombo. Josaphat Kamatoto reached out to Samuel Maharero and the military leadership to ensure that Kuhlmann was promised safe escort to Okahandja. Putting his own life at risk, Josaphat Kamatoto guided Kuhlmann and the group of Germans, including German settler women, on their trip to safety and protected them against the angry crowd of Ovaherero. In a dramatic rescue operation, he escorted the ox wagon with the Germans almost right up to the headquarters of the colonial troops in Okahandja.

But despite his importance for the mission society and the colonial power, despite his international experience in Germany, he finally shared the same fate as thousands of his compatriots: after the Battle of Ohamakari, Josaphat Kamatoto and his family died of thirst in the Omaheke during the extermination chase of the German colonial army.

Evangelists of Namibia

Evangelists of Namibia